A Garden Path. In conversation with Marc Mulders

2025, Anne van Lienden, interview uit A Garden Path

On a grey winter day I travel southward to the country estate Baest, an idyllic place in North Brabant where Marc Mulders has lived and worked since 2008. There it is cold and wet, the wind raw, while sunlight seeps through greyish cloud cover and the garden, fields and edges of woods seem only to consist of brownish hues. We walk past the house to his studio. The large stable doors stand wide open; this is where Marc works, at the threshold of the indoors and outdoors, also in winter. I look inside and my eyes need to adjust quickly to the bright colors of his paintings. They could be described as abstract-impressionist. No greater contrast with the limited brownish black palette of nature at winter's end seems possible.

Marc, pointing to the painting on the easel, says:

‘This painting, I'm really happy with it. We should definitely hang this in the Singer Laren exhibition. It's called A Garden Path, and has the subtitle The gardener is gone.’

Anne: ‘Last fall you exhibited the series The gardener is gone at NQ Gallery in Antwerp. It preceded your most recent works titled A Garden Path. Could you first tell a bit more about The gardener is gone?’

Marc: ‘The series was carried along by a wonderful quote from Bob Dylan – “there's no one here, the gardener is gone” – from his song Ain't Talkin'. His apocalyptic song combines well with that series which has a certain melancholy atmosphere. It's about tragedy, or let me put it this way: last winter I was painting and it wasn't going well. There was nothing but rain, rain, rain, every day. The garden flooded, the basement flooded and trees died. Later the field sown with flower seeds failed to come up, and piled on top of that was the desperate situation in the world. In that grey area, in that mood, I forced myself back to paintings from the 1990s in order to direct flowers into the form of a crucifix and the like. I sought support, as it were, so that I could continue working from nature.’

Anne: ‘Did you feel as though you had lost it, that support?’

Marc: ‘Yeah, it felt that way...absolutely, as if I had lost it. And then, when March came, fortunately the iris blossomed again, and the gladiola, the rose, the poppy, my favorite flowers. They showed their hearts. At that point I heard Bob Dylan's wonderful song about the gardener, symbolizing God, who tends the Garden of Eden. Dylan sings about the gardener having left us. I thought, yes, that's exactly what I'm experiencing. I'm still, uh...’

Marc falters halfway through his sentence.

Anne: ‘A believer?’

Marc: ‘Precisely, a believer. But then in the process of painting, praying that way. I've left the church, but I see the divine in nature, from a Christian/Buddhist perspective. When I talk about faith – that may sound a bit pedantic – I feel a strong affinity with the beautiful words of Vincent van Gogh, how he wrote about faith, that universal Christian/Buddhist principle, in a way that's not at all narrow or small or short-sighted, but anyway...

It was that very combination of the flower's heart revealing itself again and this wonderful phrase in the lyrics of Bob Dylan that prompted me to paint. A series of larger works came about, and I named those after the quote “There's no one here, the gardener is gone”. All those paintings are upright, and in them it's as if there's a turbulence, a spirit present in nature, among the blotches of flowers. As if he were here: g,o,d, GOD. Having left his echo with the message: “try harder to do your best, to be a better person, you've got to look for it in nature, and practice”.’

Anne: ‘During that period, when you had just found the momentum of painting again, Jan Rudolph de Lorm and I came along, asking if you'd want to exhibit at Singer Laren. At the site where, roughly a century ago, William and Anna Singer had a sumptuous garden created next to their house in the artists' village Laren. In 2017 Piet Oudolf made a new design for the garden. Your paintings will be shown in the gallery that has wide windows overlooking the garden. In this way your works will engage in a dialogue with the museum garden. That immediately gave rise to a new development for you, didn't it?’

Marc: ‘Yes, when that wonderful new adventure at Singer came my way, I knew right away that, contrary to these vertical canvases, they would need to be horizontal ones. The melancholy period had come to an end and, because I'm grateful for also being able to relate to the beautiful garden by Piet Oudolf and Laren's luminists, I immediately thought: this is going to be a celebration of color. The new paintings, as I saw it, would have to have a landscape-like appearance; but the horizontal format is a nod, in gratitude, to the late works of Claude Monet, his horizontal water lily paintings that embrace you at the Orangerie in Paris. Those works by him, along with those of Willem de Kooning and Helen Frankenthaler which I admire, were part of what made abstract expressionism possible. Also because I find that the vertical canvases of The gardener is gone have a confrontational format; the landscape format, to me, symbolizes an embrace, the greatest gesture one can experience.’

Anne: ‘Did your emotions also pivot at that moment?’

Marc: ‘Yes, that distressing, menacing feeling that I was experiencing in the winter of 2023-24, had settled. Because the flowers were back, I again had a more pleasant sense of hope thanks to beauty and trust in the cycles, the rhythm of nature. A feeling that, after the tragedy on the global stage, your children or grandchildren could become a new flower-power generation.’

Anne: ‘How wonderful... So once the summer of 2024 arrived, your thoughts revolved around the garden at Singer Laren and Piet Oudolf's design sketches for it. One of his books is right here within easy reach. It's already covered with oil paint. What is it about his gardens that inspires you?’

Marc, pointing to a brushstroke in the painting on the easel:

‘Look, this is what I call a “designer stroke”; it shines, it's both modest and prominent thanks to the quiet areas of orange, pink and grey around it. This stroke has value because it's almost surrounded by a mini garden. Here you see that I've made a sweep in wet green paint with a fan brush, creating the suggestion of flora and fauna.

Precisely what I do I can also recognize in the gardens of Piet Oudolf. He can let a particular plant shine, an echinacea for instance, because the quiet hues and textures of other types of plants around it allow him to do so. That, to me, is essential, and I see it as an distinct similarity between my work and his gardens. Perhaps that sounds a bit pompous, but we can just forget it then.’

Anne: ‘In A Garden Path the element of the path also comes into play. Is that important when you paint, that you walk around in the garden, among the flowers, that you're in direct contact with nature?’

Marc: ‘Definitely, I've done that in a variety of ways. When I came to live here, I asked the farmer to plough everything and sow wildflowers, across an area nearly as big as two football fields. So I had an entire ocean of flowers here. In some places it grew high, and with a brush cutter I made paths there. You then walk down a narrow path, just barely getting through, and become completely absorbed in the colors and scents and sounds. Because that mix of seeds includes grains and buckwheat, which attracts lots of butterflies and bees. You hear them buzzing. That's enchanting, intoxicatingly beautiful. When I walked there, it was like being on a trip, but without drugs!

Piet Oudolf also creates paths in his gardens. He designs them with a certain sensuality, a meandering path through or around oval or circular beds of plants or grasses. In the Oudolf Garten on the Vitra Campus in Weil am Rhein, for instance. There a really beautiful example of this can be seen.’

Anne: ‘I now see, even though it's winter, that your garden has changed since the early years. Have you started to garden differently?’

Marc: ‘Yeah, eventually I sort of had to abandon the idea of the flower meadow, since the whole thing is flattened after a single downpour. So I thought, I'll have to divide it up more, and in the process I put in more perennials and created circles for flowers that are sown. Which is why I say a bit wistfully: if only I had dared to ask Piet Oudolf to come and do that. This would have been something special. I've always just messed around, since I know absolutely nothing about gardening. But while exploring, I've been able to experiment with the garden for the past fifteen years. Fortunately, I've taken photographs over the years, and these serve as a journal of my quest. They clearly show just how big the difference is with the flowery paintings I was making seventeen years ago at my studio in the convent school in Tilburg. There I set out buckets full of flowers that I had delivered from the flower auction in Aalsmeer. I looked at a few of them and distributed those across the surface, as it were, in the form of a floral pattern. It was fairly abstract, but as a viewer you could see: these are roses, irises. They were still recognizable then, and now that isn't the case.

When I came here I saw a flower in the pasture and thought: I won't need to buy flowers anymore; they're either already there, or I'll sow them myself. As I looked out at them, I no longer saw the blank wall of my studio in the distance but the edge of a forest. So if I no longer would focus on the heart of the flower, which has symbolic value to me, which has the tragic quality of fragility and of blossom and of a wound as well... If I would take the space of the flower and extend it to that edge of the forest, it would become more conceptual. That space is abstract, and has a different kind of spirituality which is more about hope and the future. This was really a great discovery, and as a result my paintings started to become less figurative, more abstract.’

Anne: ‘And how has it been going since then?’

Marc: ‘Then you keep on struggling as a painter, which is why I'm so happy with this painting in front of us. Then I suddenly feel...though it might sound like a cliché, but I couldn't have produced this work when I was twenty, thirty or forty years old. By this I'm not at all trying to imply that the older you get the better the works you paint become. It can also go in the very opposite direction. Over the past few months, I've destroyed quite a few canvases in fact. Fortunately, this one does have a certain something. A whole lot comes together in it, thanks to the focus on the gardens, the sketches of Piet Oudolf and Laren's luminists. Just as with a singer-songwriter, a number of sources of inspiration get you going in a positive way.’

Anne, standing next to the painting on the easel: ‘When did you make this painting?’

Marc: ‘In November.’

Anne: ‘So there weren't any flowers left in the garden.’

Marc: ‘No, the motif doesn't have to be literally present anymore, just in my memory, along with memories of gardens made by Piet Oudolf and the open books lying around. I keep looking at the books, at works by the Laren luminists, and build up a reservoir of memories. Also from forty years of painting... If I'd wake up on another planet tomorrow morning and never actually see another garden again, I'd still have enough in my mind to keep on painting the garden for, say, another twenty years.

Because I'm into that abstraction, too. Willem de Kooning, at a certain point, moved to Long Island. There he began to produced those magnificent landscape-like paintings, but before that, in New York City, he painted something like a counterpart to those later works.’

Anne: ‘Here you also have a fairly dark painting, in lilac-purplish hues, a Nocturne. Can you tell me more about this one?’

Marc: ‘I started painting the Nocturnes eight years ago, when I had an exhibition at Piet Hein Eek's gallery. He built my outdoor studio; its exterior had to be black. At the time we had a conversation about the evening landscape and the term nocturne, also in music. Every now and then the Nocturnes come back. I did these around Christmas, when it gets dark very early, and during that time it was very foggy – and grey all day. Then I was listening to music again, that wonderful song by Jimi Hendrix, Purple Haze. It's about some drug, but to me it's also an atmospheric condition in painting. During those grey days, while I stood out in the cold painting, I really took pleasure in bringing out that lonely blotch of color in the fog, like the loneliness of a certain shade of color in a Piet Oudolf garden. Not everyone finds the dying of plants in autumn and winter an appealing sight, but Oudolf does in fact. There's a certain emotionally charged quality about this, a kind of pathos.’

Anne: ‘And you still manage to get so much color out of it.’

Marc: ‘Yes, exactly... To me, a transparent spot like this, the opening in the composition, does have importance. On those misty grey days I can't come up with Barbie colors, you might say – that would go too far. The sun really has to shine for that.’

Anne: ‘But even so, you do want to show it in A Garden Path.’

Marc: ‘Yes, in fact I believe it's essential to show this work at the Singer, as a pendant to the series. This is how I also regard the fish that I painted in some sort of trance. Last year, while I was working on the series The gardener is gone, which is about melancholy, I wanted a kind of shape to be present in the works, to show that dialogue is nevertheless possible. That's when, from my imagination, I painted a fish – the Ichthus, a secret symbol for Christ in the catacombs. Last December I painted more works with fish, again from my imagination. Then it especially concerned the wound that the fish has, its curled scaly skin, which reveals its innermost layer. It's about the tragic nature of life and death. One second you're alive, the next you're not there anymore. It's sad...the head points upward, he's gone. It's almost an emblem. This strikes me as being, with the figure, a nice work to include at the Singer. To me it's the wound, a reference to the situation in the world, the wound of today.’

Anne: ‘And yet this fish emerges from a flowery, hopeful environment consistent with the series A Garden Path – from the forms, textures and colors of the garden.’

Marc: ‘Yes, absolutely!’

Anne: ‘At Singer Laren you've already seen, in the past, a number of paintings by the Laren luminists, and those inspired you with A Garden Path too. How does that go with you?’

Marc: ‘One of the reasons why I manage to achieve what I do as a painter is that I've spent hours, days in the library and in museums. As a young painter you go on a voyage of discovery. During my art school days, I discovered Willem de Kooning. I then saw him in a documentary in which he first does something on the canvas and then goes off, ten meters away from the painting, to sit in that nice chair and look at it for a long time. This was when I realized that expressive painting does not at all have to be in the manner of Karel Appel, as you see in the famous film by Jan Vrijman. But this circumspection, this precision, that's what it's about...To me, it was a real eye opener. To see that an expressive gesture almost holds a zen-like attitude. The word 'voodoo' has importance for me as well.’

Anne: ‘Explain!’

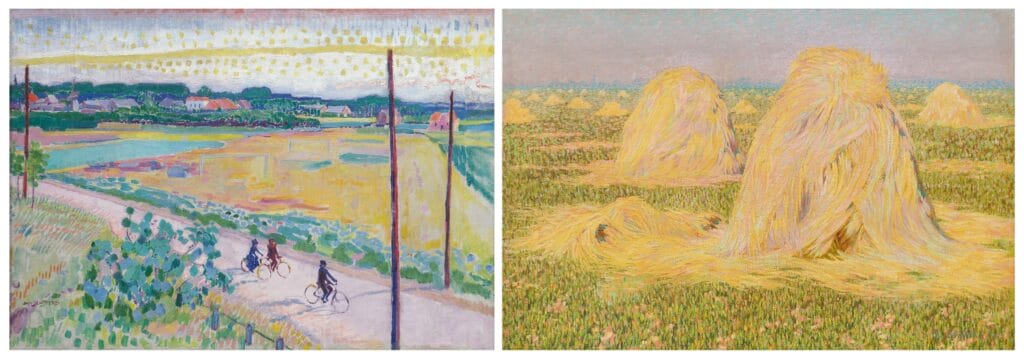

Marc: ‘On my voyage of discovery Willem de Kooning had a lot of importance, and after that I discovered Helen Frankenthaler. At art school I became acquainted with Henri Matisse and the Fauves. The Laren luminists do echo the French fauvists of course. All of these artists were very welcome to me, since I had always sought, or had been open to, not so much the tradition of portrait painting or a literary narrative genre, but the 'voodoo' element. By that I mean that, as a painter, you attempt to gain power over the space before you, nature. And the enormity, the mystery of nature. Joseph Beuys did that...at a certain point he created a 'sun cross'. For me, as a painter with a brush, in the tradition of the great Vincent van Gogh, the Laren luminists were a discovery because they didn't have to lower themselves to a cheap expressionistic gesture. I mean: that as a painter you're almost expressing an incantation. I got that sense with Co Breman, too, who produces basically neat, quiet paintings, but they do have that 'voodoo' element. He hasn't put those rays of sun in an overly pathetic or expressive gesture, but rather in painful precision. In showing the normal, it becomes really terrible, in a good sense. That painting with the haystacks is a great example of that.’

Anne: ‘You mean that he, in his aim of rendering the shimmering of light, visualized something that transcended visible reality?’

Marc: ‘Yes, those mounds are more than haystacks to me...they're also shapes, figures. An apparition of nature, like a beautiful tree trunk that can also stimulate the imagination. If I had stood there in 1905 I would also have liked to attack that landscape-like scene with a promise of abstraction. And vice versa, if he had been walking around here now as a young painter, then he would have tried to lash out at the landscape in today's tradition. And that's where I feel a certain affinity with Laren's luminists.’

Anne: ‘If you put it that way, I'd say Jan Sluijters was very spiritual too, at least when he was painting in Laren. There was something shamanistic about the way in which he wanted to ward off, as it were, the sensation he experienced on seeing the landscape and the bright October sun, or the mysterious light during a lunar eclipse. Some say there is strong earth radiation in the Gooi region, causing the force of nature to be particularly palpable there.’

Marc: ‘And don't forget theosophy and anthroposophy, which were a way of life at that time. If I had been standing there with my easel, alongside Sluijters and Breman, I would have painted a luministic work too; but I have abstraction, the legacy of Monet, De Kooning, Frankenthaler. These are painters who have always been with me. For this reason I consider it an honor to be exhibiting in the home of Laren's luminists. Also to know that in the other exhibition being held at Singer, Lokroep van de natuur (The Lure of Nature), one of my paintings will actually hang next to one of them, together.’

Anne van Lienden

translation: Beth O'Brien